The Symbolic Return of The Dead in Ejagham Funeral Tradition

Overview

Among the Ejagham people, death is not merely a biological event but a transition that must be ritually navigated to preserve the integrity of lineage, identity, and ancestral belonging. Even when an individual dies far from home and is buried outside their native village, the community insists that the spirit must return. This belief is rooted in a worldview where land, ancestry, and personhood are inseparable. The ritual that accomplishes this symbolic return is known as Ekpaeku, one of the most profound and enduring expressions of Ejagham cosmology.

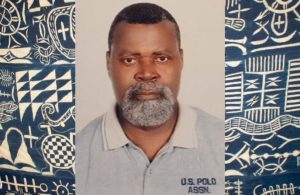

Barr. Akabum Agbor from Inokun, Ejagham Njemaya

This narrative presents a comprehensive account of the Ekpaeku ritual, drawing from oral testimonies, contemporary observations, and the detailed procedural knowledge preserved by custodians of tradition. It also incorporates the authoritative clarification provided by Akabum Agbor, a direct descendant of Ntuifam Asek Ntui‑Etem, founder and first Chief of Inokun village. Together, these perspectives illuminate the cultural logic, emotional depth, and communal responsibility embedded in this ritual.

The Cultural Logic of Ekpaeku

In Ejagham thought, a person’s life is inseparably tied to their ancestral land. To die outside one’s village is to risk spiritual displacement. Thus, when an Ejagham man or woman passes away and is buried elsewhere, the funeral rites remain incomplete. The deceased must be symbolically transported home so that the remaining rites, those that anchor the spirit among its ancestors, can be properly performed.

Ekpaeku is not a symbolic gesture in the modern sense; it is a spiritual necessity. It ensures that the deceased is not left wandering in a foreign land and that the lineage remains intact. The ritual affirms the community’s responsibility to its members, even in death.

Ritual Objects: The Material Body of Memory

The Ekpaeku is composed of a set of carefully selected ritual objects, each chosen for its symbolic weight and its role in transforming ordinary materials into a living representation of the deceased.

- Ekpa (Mat): At the heart of this assemblage is the Ekpa, a raffia grass floor mat woven from dried palm fibers. In everyday life, such a mat serves as a place of rest and domestic grounding, but within the ritual it becomes the physical stand‑in for the body itself. Its organic texture and earth‑bound nature evoke the final return of human life to the soil and to the ancestral realm.

Ekpa (Mat)

- Efo-ebun (Loincloth): Beneath this mat lies Efo-ebun, a new, unused loincloth, a cloth that has never touched another body. Its freshness symbolizes purity, dignity, and the untainted transition of the deceased into the ancestral world. In the same way a corpse is dressed with care and respect, the loincloth functions as the ceremonial garment of this symbolic body, ensuring that the deceased is honoured with the same propriety accorded to a physical burial.

Efo-ebun (Loincloth)

- Monitemi (Kitchen Knife): Beside the wrapped mat is placed the Monitemi, a kitchen knife drawn from the intimate sphere of domestic life. This knife represents the everyday labour, protection, and continuity of the household. It carries the memory of the deceased’s contributions to family life and serves as a metaphoric companion on their journey, invoking both spiritual safeguarding and the enduring responsibilities of lineage.

Monitemi (Kitchen Knife)

- Ibum (Palm Frond): The entire assemblage is bound together with Ibum, the tender yellow palm frond taken from the unopened heart of the palm tree. Because it comes from the untouched center of the plant, the frond embodies freshness, innocence, and spiritual cleanliness. When used to tie the bundle, it gathers the disparate elements into a unified whole, sealing them into a coherent ritual body. The palm’s association with resilience and continuity further reinforces the idea that life persists even in death.

Ibum (Palm Frond)

This transformation takes place at dawn, a moment of transition between night and day, symbolizing passage between worlds. The loincloth is folded neatly to form the base, the Ekpa is wrapped and placed upon it, the Monitemi is positioned beside it as though accompanying a real body, and the Ibum is used to secure the entire structure. Once tied, the bundle ceases to be a collection of objects. It becomes the Ekpaeku, a material body of memory, treated with the same reverence, caution, and emotional gravity as a physical corpse. It is carried, invoked, and honoured as the deceased themselves.

The First Carrier: Voice of the Dead, Vessel of the Living

The ritual begins very early in the morning. An elderly woman, or any woman designated for the task, lifts the Ekpaeku onto her head. As she walks, she calls the name of the deceased and chants the traditional invocation:

- “Bak ekweri oooo” – (come, let us go home.)

- “Nne akah etek aneh akweri ejeh.” – (When a person lives in another’s land, he must eventually return to his own.)

This invocation is both a summons and a reassurance. The bearer becomes the emotional and spiritual vessel of the deceased, guiding the symbolic body home with her voice, her steps, and her tears. Her grief is not a private emotion but a ritual expression of memory and duty.

The Journey Begins: Movement Through Sacred Space

The Ekpaeku ritual begins with a deliberate and symbolic act of placement. The Ekpaeku is first taken to the outskirts of the village, positioned in the direction of the deceased’s home village, and left there for a period that may last several hours. This pause is not incidental; it marks the spiritual threshold between the land of residence and the land of origin. In Ejagham cosmology, this moment signifies the deceased’s readiness to begin the homeward passage and acknowledges the transition from one realm of belonging to another.

After this initial placement, the carriers may briefly return home to eat and prepare themselves for the journey ahead. This interlude allows the participants to gather strength, physical, emotional, and spiritual, before undertaking the solemn procession.

When the time comes to depart, the order of movement reflects the gendered structure of ritual authority in Ejagham society. A senior man, or any designated male, walks at the front of the procession. Immediately behind him follows the woman bearing the Ekpaeku upon her head, with the remaining members of the escort team walking behind her. This arrangement underscores the complementary roles of men and women in guiding the deceased through the final stages of their symbolic return.

Throughout the journey, the bearer must periodically call out the name of the deceased, especially when crossing streams or rivers. Water crossings hold deep spiritual significance in Ejagham tradition, representing liminal spaces, thresholds between realms. By invoking the name of the deceased at these points, the bearer reaffirms the connection between the living and the departed, ensuring that the spirit remains guided and anchored throughout the passage.

The Ekpaeku Moves in Sound and Spirit, Carried by Okang‑Kang Rhythms and Ibang Blasts.

A further essential element of the procession is the presence of ritual sound. As the bearer walks, another woman accompanies her, playing the iron double‑gong known locally as Okang‑kang. The rhythmic, resonant tones of the Okang‑kang are more than musical accompaniment; they function as ritual signals, announcing the movement of the Ekpaeku and reinforcing the solemnity of the spiritual journey. The sound marks the procession as sacred, alerting all who hear it that a passage of ancestral significance is underway.

The ritual is often enriched by the inclusion of the Ibang horn, typically played by a man. Its sharp, penetrating blasts herald the approach of the Ekpaeku delegation as they near the village. The Ibang serves as a ceremonial announcement, calling the community to attention and preparing them to receive the symbolic body with the dignity, reverence, and collective awareness befitting an Ejagham homecoming.

Ibang (Horn)

Together, these movements, sounds, and invocations transform the journey into a sacred procession, one that binds the living, the dead, and the ancestral world in a single, continuous thread of memory and belonging.

Arrival in the Next Village: Hospitality and Ancestral Law

Upon arriving in the next village, the name of the deceased is called once more. Unlike the initial village, the Ekpaeku does not stop at the outskirts; it enters the village directly. The hosts may welcome the procession with food and drinks, or with drinks alone, depending on their custom.

It is the host village’s decision whether the Ekpaeku will spend the night. If it does, the symbolic body is placed on a small table in the host residence until the next morning. This overnight stay is treated with the same solemnity as if a real corpse were lying in state.

At dawn the following day, the Ekpaeku is taken again to the outskirts of the host village, following the same procedure as at the place of burial.

Nsek‑Eku: The Escorting Tradition

The host village traditionally assigns one or two members of their community to accompany the Ekpaeku to the next village. This escorting practice is known as Nsek‑Eku. It symbolizes inter‑village solidarity and ensures that the deceased is never left unattended.

This process continues from village to village until the Ekpaeku reaches its final destination, the ancestral home of the deceased, where the remaining funeral rites can be properly performed.

A Historical Lesson: The Ayaoke Incident

The seriousness of Ekpaeku protocols is illustrated by a well‑remembered incident in Ayaoke. An Ekpaeku traveling from Otu to Inokun was left at the village boundary while the carriers went to inform the elders. Strangers, traders unfamiliar with Ejagham customs, mistook the bundle for merchandise and stole it.

The village reacted immediately. Search teams were dispatched along all bush tracks, the ancient routes connecting Ejagham settlements. One team intercepted traders on the Ayaoke–Inokun path and recovered the Ekpaeku from their luggage.

This episode remains a powerful reminder of the vigilance and communal coordination that once characterized Ejagham society.

Cultural Significance and Contemporary Challenges

The Ekpaeku ritual embodies core Ejagham values:

- Belonging: No member of the community is left spiritually displaced.

- Continuity: Life and death are connected through lineage and land.

- Collective Responsibility: The community safeguards the journey of the deceased.

- Memory: Objects associated with the deceased become vessels of identity.

- Order and Protocol: Inter‑village relations are governed by respect and ancestral law.

Yet modern realities, migration, motorable roads, globalization, have altered how Ekpaeku is practiced. Today, Ekpaeku may travel by road from distant cities or even from abroad. The core principles remain, but the logistics have changed.

This shift underscores the urgency of cultural preservation. Ejagham heritage has suffered from erosion, dilution, misinterpretation, and in some cases extinction. The community’s commitment to Documenting, Digitalizing, and Disseminating its traditions is therefore essential.

Deduction

The Ekpaeku ritual is more than a funeral custom. It is a declaration of identity, continuity, and belonging. It affirms that no Ejagham person dies alone, no spirit is left wandering, and no lineage is forgotten.

Through Ekpaeku, the living escort the dead home, reaffirming the unbroken bond between past and present. In preserving this tradition, the Ejagham people reclaim not only their heritage but their cultural sovereignty, ensuring that future generations inherit a legacy rooted in dignity, memory, and ancestral wisdom.

Part 2 Loading ….

Ekup na Nkad